|

In the Governor's office resides a mural that has generated accolades.

It's also a mural that has generated controversy, protest, draperies, a painting in rebuttal, multiple legislation, an attorney general's opinion, and finally, an order of the Governor to obfuscate the painting from view until such a time is can be removed without causing it permanent damage - a time which might not exist in our lifetimes.

That mural is the famous (or if you prefer, infamous) Edwin H. Blashfield mural originally entitled Spirit of the West.

Who is Edwin Blashfield? At one time called the Dean of American Mural Painters, his paintings and murals

can be found in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and in the South Dakota State Capitols. Pictured at the right is a mural painted by Mr. Blashfield that adorns the Governor's Suite in the Minnesota State Capitol.

You can also find his murals in libraries in Detroit, Kansas City, the New York City College (now C.C.N.Y.), M.I.T., Grove Academy of Athens (Georgia), Baltimore and Cleveland court houses, and private homes and businesses.

Blashfield's resume also boasts the obverse of the 1896 Two Dollar Bill...

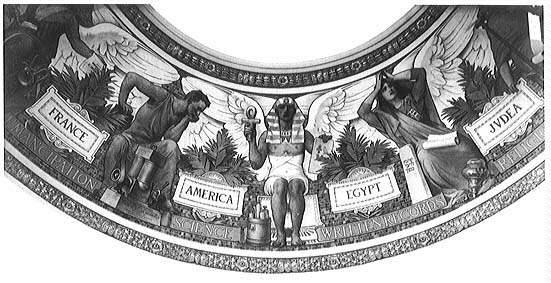

as well as the dome in the Jefferson building of the Library of Congress entitled "The Evolution of Civilization"

But in South Dakota, this artist is best known for his work "Spirit of the West"

In describing it, Doane Robinson related in the South Dakota Historical Collections 1910 that "South Dakota is represented by a beautiful woman, in the spotlight, with the figure of hope floating over her head and pointing forward. The woman, holding the bible, is the Spirit of the West - the title of the picture.

Trappers and settlers are beating back and overcoming the Indians who are clinging to her garments, attempting to impede her progress.

The man with the brown hat and beard, holding the gun, represents the US Army. The man with the pistol represents the Homesteader.

The Army and the homesteaders are pushing the Indians down to the ground, thinking they have them conquered.

Outlawry, or the evil spirit, represented by a dark and hooded figure seeing civilization coming into the country, covers his face with his hands and scuttles away into the darkness.

At the top of the picture is the guiding angel, pointing the people to come to this western country and settle.

Just below are the covered wagons, moving through the badlands into the Black Hills, and on into Wyoming and Montana.

Mr. Blashfield traveled from his studio in New York to Pierre to assure himself that his masterpiece was properly mounted and that the decorations of the room were in harmony with it. He regards it as one of his great works and said of it that he never has excelled its technique."

This painting of an entirely original theme earned him the gold medal of the Architectural League - one of the highest honors ever accorded an American painter. This nine feet square painting also earned him accolades from the April 1911 issue of the Western Architect magazine who called it "one of his best pictures."

But in the times since, it's history and interpretation have invited controversy, and as you might guess from the Robinson description, it has invited a degree of criticism from South Dakota's Native American population for it's depiction of manifest destiny displacing native populations.

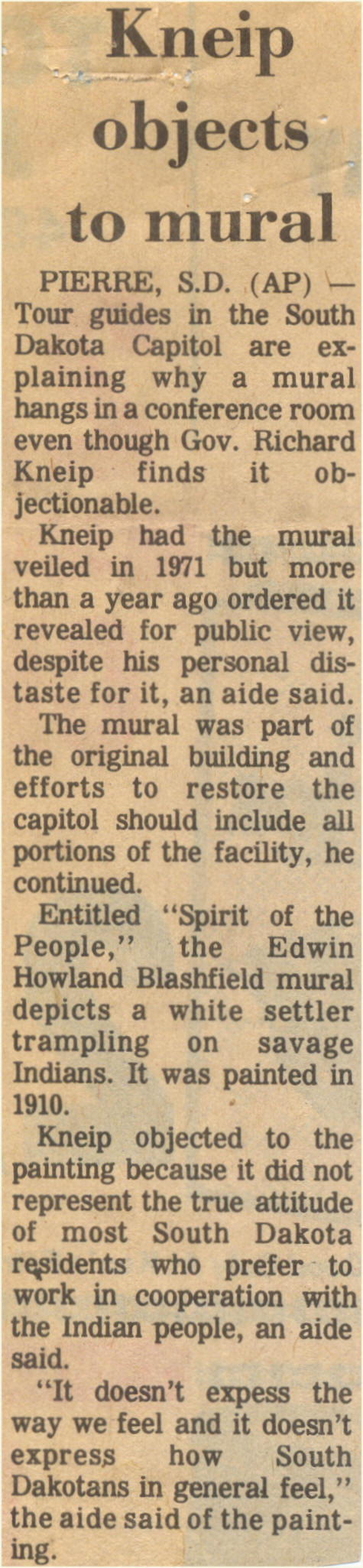

At the end of the 1960's and early 1970's, as Native Americans in South Dakota were asserting themselves politically and culturally, the Blashfield painting became a focusing point. Newly elected Governor Rchard F. Kneip found the mural objectionable and had it veiled in 1971, so only a drapery would be visible by visitors to the Governor's Reception area.

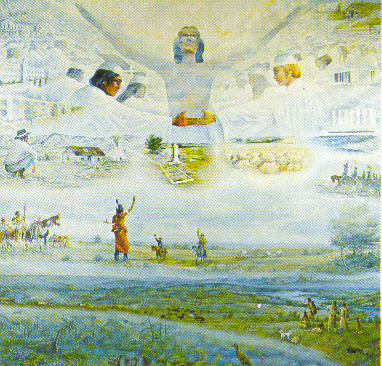

At the same time, he commissioned a mural by Paul War Cloud Grant titled "Unity through the Great Spirit." This painting served as a contrast to the mural and either could be viewed by visitors to the Governor's office once complete.

Subsequently, in about 1976, a major restoration of the State Capitol commenced with a goal of returning the majestic building to it's original state. Part of the restoration included the Governor's office, returning the Blashfield painting to full public view without draperies or other art acting as covering.

The South Dakota news media noticed the fact that the mural was returned to view, and a series of stories ran noting that Governor Kneip "found the mural personally distasteful, and that it did not represent the true attitudes of most South Dakota residents who prefer to work in cooperation with the Indian people."

But, "the mural was part of the original building, and efforts to restore the capitol should include all portions of the facility."

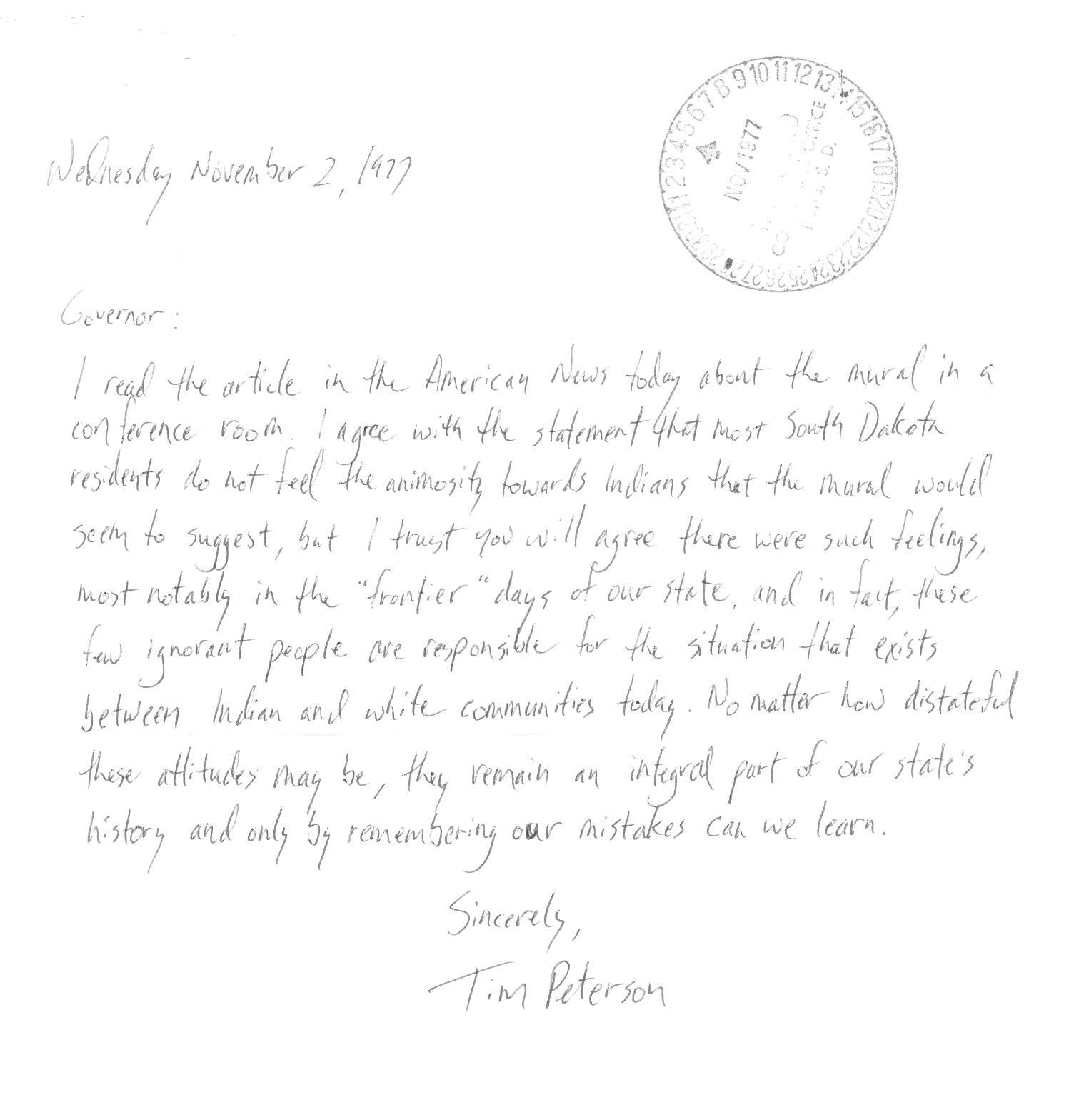

About the time this story ran, in November of 1977, a Aberdeen college student, Tim Peterson, wrote the Governor and expressed his feelings on the matter.

Peterson wrote:

Governor:

I read the article in the Aberdeen American News today about the mural in a conference room. I agree with the statement that most South Dakota residents do not feel the animosity towards Indians that the mural would seem to suggest, but I trust you will agree there were such feelings, most notably in the "frontier" days of our state, and in fact, these few ignorant people are responsible for the situation that exists between Indian and white communities today. No matter how distasteful these attitudes may be, they remain an integral part of our state's history, and only by remembering our mistakes can we learn.

A staff member brought Tim's suggestion to the Governor, who put his stamp of approval on placing a plaque next to the mural unofficially changing the name of the painting from "Spirit of the West" to "Only By Remembering Our Mistakes, Can We Learn."

During the 1980's after the Capitol Restoration had been completed under Governors Bill Janklow and George S. Mickelson, it was noted that the unofficial title had lapsed over the intervening years in favor of the original "Spirit of the West."

A State Senator at the time, Thomas Shortbull, began attempts in the mid 1980's to have the portrait removed from public view in the Capitol. At this time, Governor Mickelson announced a year of reconciliation between the people of South Dakota, and as part of it, he went to the Legislature and made an official name change of the painting to "Only By Remembering Our Mistakes, Can We Learn." formalizing what Governor Kneip had done unofficially several years before.

But even the renaming of the painting didn't erase the controversy, as detractors persisted in their demands that the painting be covered by draping, despite the requirements of the Capitol restoration mandating that it remain in it's restored state.

Shortly thereafter, South Dakota's media as well as others including the South Dakota Peace and Justice Center took up the cause with various protests being organized. Some used inflammatory language beyond what can be documented at any time to artistic description. Whether the affronts were real or imagined, during the 1990's the painting often served as a focal point for race relations in South Dakota.

In 1994, Senate Bill 252 was passed, which was designed to have the painting removed. However, this new law conflicted with the pre-existing law which authorized the Capitol Complex Restoration and Beautification Commission to restore the Capitol.

Attorney General's Opinion 94-14 was issued in response to the plea to determine the controversy between the two law's conflicts. Ultimately, because the mural could not be removed with present technology without causing irreparable damage, as well as then Governor Miller's concerns over removal or covering the art as being seen as an act of censorship, the Legislature's Executive board dropped the matter.

In 1997 as Bill Janklow returned to head the Executive Branch of Government, the mandates of 1994's SD 252 were brought up again as various groups began protesting the mural again.

Marie Randall, a Lakota woman who didn't own a car, hitched a ride to Pierre to view the mural for herself. As she later related to Governor Janklow in a telephone call: "The mural is beautifully done. And yet, to us it is a bad picture, I (don't) want the young people to see this. The painting may show what once was in South Dakota. It doesn't show what is and it shouldn't show what can be."

With that, Governor Janklow made the decision to cover the mural with conservation approved methods behind a wood cradle, with a note behind the sheetrock placed over it noting what the painting is, and why it is covered.

Even covered, the painting remains controversial to this day, and will likely remain covered until some point in the future when restoration efforts are considered once again at the State Capitol.

At one point during the battles over the mural, Victorene Blashfield, a relative of Edwin Blashfield who was also of Native American descent, offered the following quote in its defense. It's symbolic of why South Dakotans have such conflicted feelings over the painting and the eternal debate over whether it's better to display it and remember, or to cover it and strike from our minds of a shameful example of our past:

"When you paint history the material is imposed upon you; You have to put upon your wall what was really present when the event to be portrayed actually took place."

- Edwin H. Blashfield, A Word for Municipal Art.

Copyright 2007 South Dakota Bureau of Administration | Frontpage-Templates.org | E-Mail BOA Webmaster

SD Home | BOA Home | Accessibility Policy | Disclaimer | Privacy Policy | Search | Feedback | Help